*This piece originally appeared in the Winter 2025 issue of the newsletter of the Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Science at The University of Queensland, at which I am an affiliated researcher*

Last year, or any year before that, you would have been unable to provide a simple answer to this simple question: “Are Australia’s threatened frogs still declining or have they recovered?” This year, you can.

If we step back a little, a question like this would be an obvious thing for a politician, a government agency or a funding body to ask. The reason is that while many of Australia’s frogs were hit hard by the introduction of chytrid fungus to the continent in the 1970s, there have been promising reports of species recovering in recent years. The beautiful Fleay’s Barred Frog (Figure 1) from the rainforests of south-east Queensland and northern New South Wales is a key example. Populations of this species have grown markedly over the past two decades, and the species has even recolonised locations from which it was extirpated by the fungus.

But what about others, and what of the collective trend? Have Australia’s threatened frogs rebounded after chytrid’s full impact, or is the pathogen — or other threats — driving ongoing declines?

Figure 1: A Fleay’s Barred Frog from the Springbrook plateau, south-east Queensland.

Enter the TSX

Questions such as these are the reason the Threatened Species Index (TSX) exists. Established in 2016 at the Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Science at The University of Queensland — through the Herculean efforts of Hugh Possingham, Elisa Bayraktarov, Ayesha Tulloch and Micha Jackson — the TSX collates monitoring data for Australia’s threatened and near-threatened taxa and estimates abundance trends. The TSX seeks to be an objective measure of change in the populations of Australia’s imperilled species, as well as a repository for all the hard-won monitoring data collected for these species. It is the only national infrastructure presently available to do either of these things and is now a key biodiversity metric for the country.

The TSX continues to grow. The index first covered birds (2018), then integrated mammals (2019) and then plants (2020). From 2021 to 2023, the index remained at this coverage, although the team were working hard behind the scenes to update existing datasets and bring in new ones.

A leap to frogs

Through 2023 and 2024, the TSX team sought to expand the taxonomic coverage of the index and it was agreed that bringing in frogs was the logical next step. There were several reasons to prioritise amphibians. First, we knew that drastic historical declines of amphibians were a crucial element of biodiversity trends in Australia. Second, amphibians have the highest rate of imperilment among Australian vertebrates, with around 30% of taxa listed as threatened or near-threatened. Third, there is extensive monitoring data available for frogs thanks to decades of work by Australia’s herpetological community.

To this end, we completed a literature review of frog monitoring in Australia and compiled a list of known monitoring programs and relevant contacts. Across 2024, we reached out to numerous herpetologists across the country, asking whether they would be willing to share their data. Thankfully, many were receptive.

When combined with data we mined from publications — using the expert coding skills of Alex Bezzina — the datasets started to accrue. We pulled the trends together in November 2024 and launched Australia’s first Threatened Frog Index in December at the annual conference of the Ecological Society of Australia in Melbourne. In total, we amassed 587 eligible monitoring datasets for 27 taxa.

So, we can now return to the opening question: “Are Australia’s threatened frogs still declining or have they recovered?” Sadly, the data we compiled suggest that Australia’s imperilled frogs continue to decline and very steeply in some cases.

Tracking declines

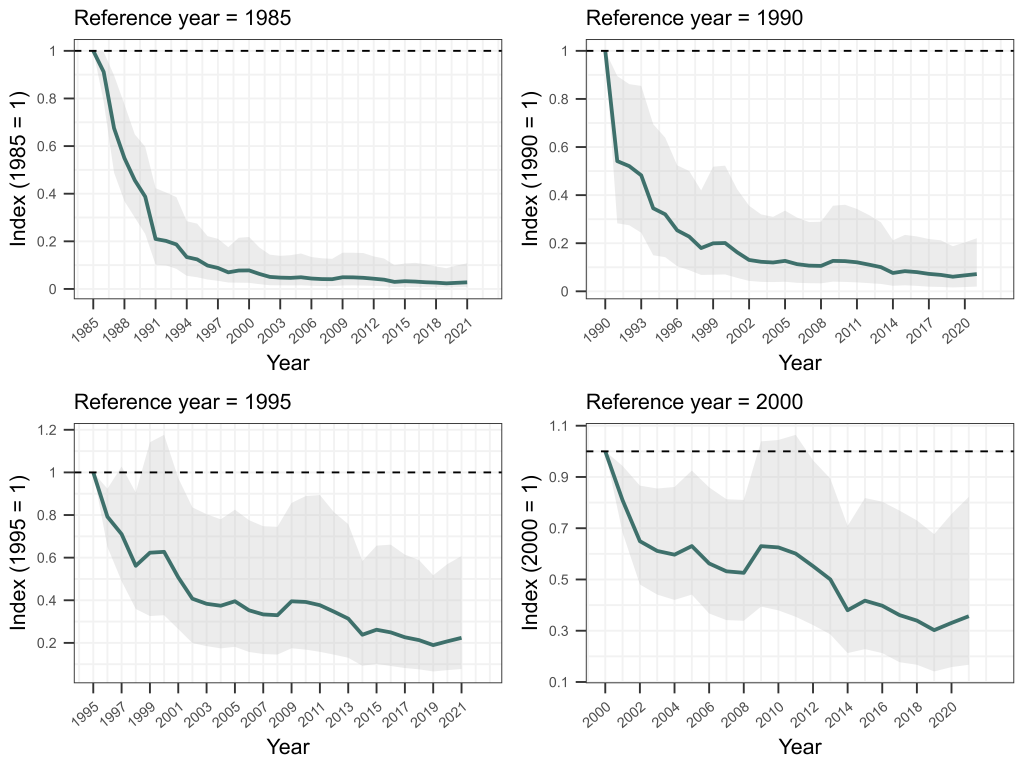

Beginning with the earliest reference year of 1985, the estimated decline in the relative abundance of Australia’s imperilled frogs up to 2021 was immense, at 97% (Figure 2). This is the largest decline among the species groups included in the TSX to date. It stems from: (1) the collapse of numerous frog populations due to chytrid fungus in the late 1980s and 1990s; (2) the numerical dominance of taxa impacted by chytrid fungus in the early monitoring datasets; (3) the lack of recovery of many of these taxa; and (4) continued decline of others in more recent years.

But what of threats over more recent decades, after chytrid epizootics dissipated? Unfortunately, the data we collated suggest declines continue (Figure 2). With a reference year of 1995, the estimated average decline to 2021 was 78%. With a reference year of 2000, the average decline was 64%. These are still very significant declines.

Figure 2: Trend estimates from the 2024 Threatened Frog Index, with reference years of 1985, 1990, 1995 and 2000. In each case, the green line shows the average change in relative abundance compared to the baseline year. The shaded areas show the confidence limits.

A range of threats

A crucial element of the ongoing decline story is contractions among frogs thought to be largely unaffected by chytrid fungus. Across the datasets we compiled, chytrid-impacted taxa declined by 53% on average between 1997 and 2021, compared with 71% among non‑chytrid‑impacted taxa. While data are limited for non‑chytrid‑impacted taxa (restricting the comparison to 1997 onwards), this surprising result speaks to the fact that Australia’s frogs face various other threats. Among non‑chytrid‑impacted taxa, declines are related to habitat loss and fragmentation, exotic pests and the cumulative impacts of climate change, including heat waves, deepening droughts and increased fire frequency and severity. For example, significant declines were evident in the key long‑term monitoring data we received for the Wallum Sedge Frog (Litoria olongburensis; Figure 3), collected since 2009 by Harry Hines and Ed Meyer. This species is not known to be impacted by chytrid, but the severe drought of 2018-20 in south‑east Queensland caused significant declines for some populations.

Figure 3: A Wallum Sedge Frog from south-east Queensland, a species not known to be impacted by chytrid fungus, but which has suffered declines during periods of severe drought.

Monitoring through space and time

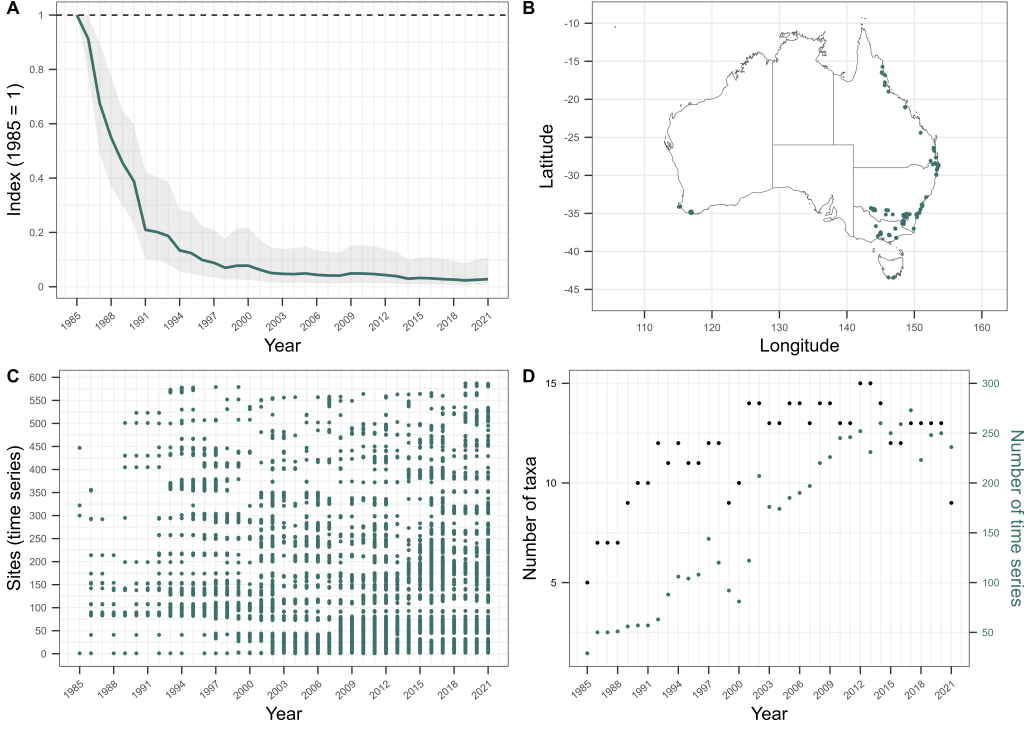

The data collated so far for the frog index are primarily from eastern Australia, in line with the distribution of threatened and near‑threatened Australian frogs (Figure 4). Tasmania is represented by a single species (Litoria burrowsae) and Western Australia by three species (Anstisia alba, A. vitellina and Spicospina flammocaerulea). No suitable monitoring data were obtained for South Australia or the Northern Territory, although they each have only one threatened frog species.

A key limitation of the current dataset is its temporal coverage. In 1985, data were available for only four taxa (16% of the total) from 29 time series (5% of the total) (Figure 4). The number of taxa and datasets grew rapidly during the 1990s as monitoring of chytrid‑impacted taxa increased, with some drop‑off in more recent years.

Figure 4: A) The 2024 Threatened Frog Index for Australia based on all data compiled on threatened and near-threatened frog taxa. The green line shows the average change in relative abundance compared to the baseline year of 1985 where the index value is set to 1. The shaded areas show the confidence limits. B) A map showing where the threatened frog data were recorded in Australia. The dots indicate repeatedly monitored sites. C) A dot plot showing the years for which monitoring data were available to compile the index. Each row represents a time series where a taxon was monitored with a consistent method at a single site in Australia. D) The number of taxa (black dots) and number of time series (green dots) used to calculate the index for each year.

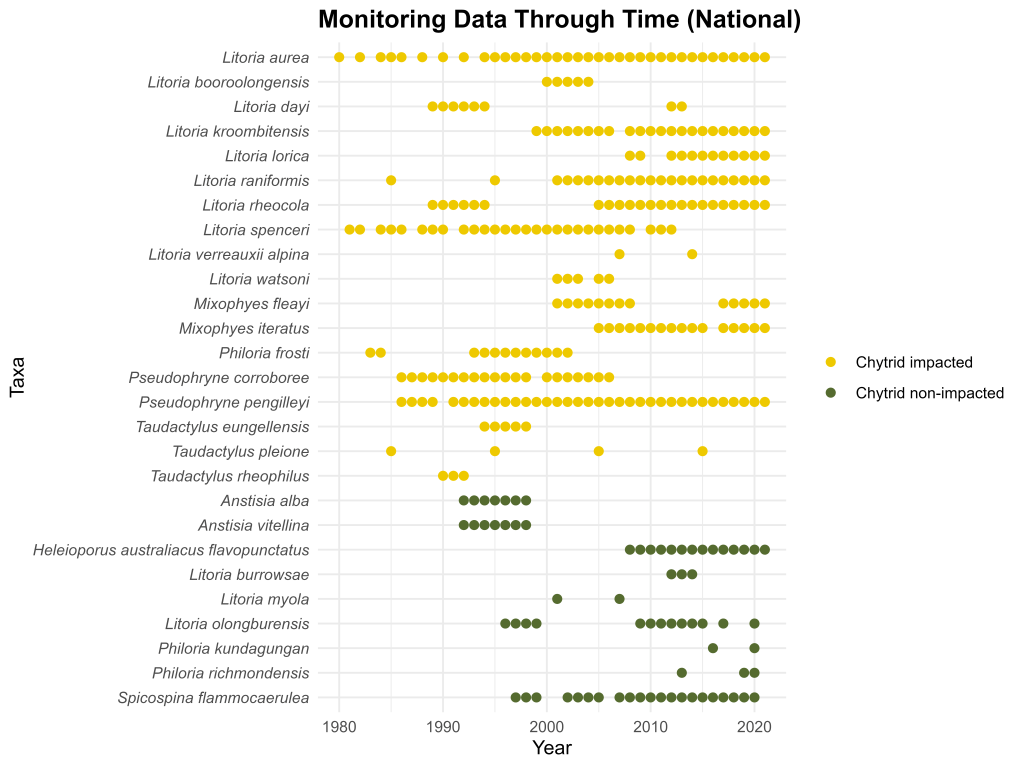

An important additional factor that must be considered when interpreting the national trend is that all data acquired before 1992 were for chytrid‑impacted taxa (Figure 5), particularly those showing rapid population crashes in eastern Australia, such as in northern Queensland. Very steep declines early in the frog index reporting period reflect this and produce the very significant overall decline of 97% when using 1985 as a reference year.

Figure 5: The temporal coverage of monitoring data acquired for threatened and near-threatened frogs across Australia for the 2024 Threatened Frog Index. Note the significantly greater amount and temporal coverage of monitoring data for chytrid-impacted taxa, and the fact that monitoring data for non-chytrid-impacted taxa are only available from 1992 onwards in this pilot index.

What’s next for the TFX?

Our new frog index suggests that, overall, declines continue to outweigh stabilisations and recoveries. While crucial information, it also presents a disheartening reality. Yet, the frog index — and the TSX more broadly — includes various datasets that highlight our capacity to recover threatened taxa. For frogs, key examples include the Southern Bell Frog (Litoria raniformis) in New South Wales and the Armoured Mist Frog (Litoria lorica) in Queensland’s Wet Tropics. Long‑term monitoring by Prof. Skye Wassens of Charles Sturt University confirms that significant investment in environmental watering has been a boon for Southern Bell Frogs in western New South Wales. In the Wet Tropics, recent translocations led by Assoc. Prof. Conrad Hoskin of James Cook University are securing the Armoured Mist Frog — a species for which all populations except one appear to have succumbed to chytrid, and which was thought to be lost forever until its rediscovery in 2008.

In 2025, we will seek to finalise the frog index, pursuing key datasets from Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria and Western Australia. Some of these datasets have been amassed over decades and are crucial to fully understanding how our threatened frogs are tracking. However, all monitoring data are valuable for projects such as this. If you have data you feel might be suitable, or if you would like to know more about the project, we would love to hear from you. Please reach out to the team at tsx@tern.org.au.